"Defence all at sea on new submarines"

Submarines are the stealthy killers in maritime warfare. They are the queens on the chessboard, the strategic game-changers. Any country has to think long and hard about messing with another country that has an advanced submarine fleet. You can't be sure there isn't one sitting quietly off your own coast or waiting in hiding to sink your ships.That Australia needs a fleet of reliable submarines is beyond doubt to our military planners. [Former Prime Minister] Kevin Rudd's 2009 defence white paper promised to build a dozen of these killers to replace the trouble-plagued Collins-class fleet of six. The paper vowed the new fleet would have "greater range, longer endurance on patrol, and expanded capabilities compared to the current Collins class".

But four years on, Defence boffins are still wrestling with the complex task of figuring out just what kind of submarine we want - and what we can afford. Time is not their friend; the Collins class is due to start being retired in just over a decade [2025], giving rise to fears of a "capability gap" in which we have too few subs - or none at all - while the new fleet is still being built.

It will be a further 18 months [2015] before the new government decides which of the two leading design options [HDW, DCNS, Navantia?] to go with, during which Australians can expect to hear much more furious argument. There is much at stake, not least an estimated $36 billion of taxpayers' money, thousands of jobs in Adelaide and Australia's current technological superiority in a rapidly changing region where Asian countries are investing heavily in their militaries.

The popular thinking in defence circles is that the new fleet should be very much Australia's own submarines, its sovereign asset. In the grandest iteration, this is nothing less than a nation-building project.

"It's going to be hard. Things will go wrong," said Rear Admiral Rowan Moffitt, the outgoing head of the future submarine program. "But it's right up there with our biggest ever national undertakings, along with the Olympics, the Harbour Bridge and the Snowy scheme."

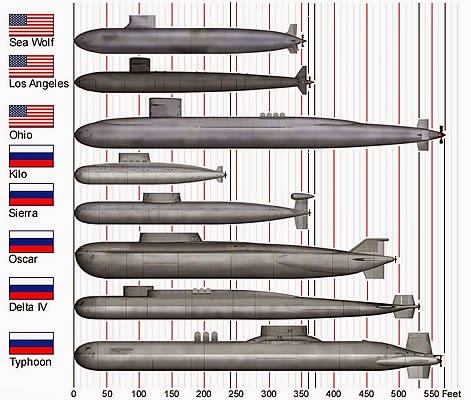

The quickest and cheapest option would be to buy an off-the-shelf European design, which would be small but modern and reliable. But this has been effectively ruled out on strategic grounds. Most experts say Australia needs a long-range submarine that could, say, patrol the South China Sea in the event of territorial disputes there or to protect shipping lanes. That means a big submarine with a big crew that can range far and wide and stay at sea for months.

The rule of thumb, says Moffitt, is that a submarine can stay at sea for about a day for each crew member on board. The Collins has a crew of 60 and can easily go to Hawaii and back. The European off-the-shelf designs accommodate crews of just 27 to 30.

"What we know with absolute confidence is that the performance of those submarines for our application ... falls dramatically short of even what Collins does. They don't have the endurance," Moffitt said.

James Brown, military fellow at the Lowy Institute, says our neighbours to the north are making strides in acquiring submarine fleets - not just big players such as China and Japan but also Indonesia, Singapore, South Korea and Vietnam.

"In 20 years' time there are going to be a lot more submarines in the region. We have to respond to that in some way and that means having a decent submarine fleet of our own."

They are also an effective deterrent to protect Australia itself, he says. If Australia were threatened, it could use its long-range submarines to launch land-attack cruise missiles at the aggressor's homeland. Then there are intelligence missions - submarines are good for sitting quietly and listening, but only if they have the range and endurance to travel far and wide.

Or as Andrew Davies, a leading submarine scholar at the Australian Strategic Policy Institute, puts it, submarines are what you use when you want to take the war up to the enemy. Nazi Germany couldn't match the British and US navies on the surface, but the legendary German U-boat took the fight right up to the east coast of the US.

"Submarines are not crocodiles you leave in the moat," he says.

Having ruled out a nuclear design, Australia will return to some form of conventional submarine that, like the Collins, uses diesel engines to charge batteries which in turn power motors for propulsion.

That leaves two options: a totally fresh design, or a so-called "evolved Collins", which takes the existing fleet, irons out its flaws and modernises parts that would otherwise become obsolete.

The smart money seems to be on the evolved Collins. ASPI's Davies calls it "sort of a no-brainer". Defence Minister David Johnston was quoted in media reports this week as saying the evolved Collins was the "leading option" - though his office afterwards played down the remarks.

It might all sound strange to the average Australian taxpayer who's been reading for years about the Collins' many flaws and annual support costs thought to be about $500 million.

But experts both inside and outside Defence say that, after years of repairs and adjustments, the Collins is now a formidable submarine. The combat system and sensors have been fixed, though the propulsion system still needs work. In recent weeks, the ASC - formerly the Australian Submarine Corporation, the government company set up to build and sustain the Collins - has cut open the hull of one boat to completely remove the engine, so it can be thoroughly overhauled.

As you read this, three Collins are at sea, which meets the benchmark for 50per cent of the fleet being operational at a given time. That's a success.

Whether the government decides on an evolved Collins design or the rival option of starting with a blank sheet of paper, [nothing is "blank". Existing Collins are full of corporate knowledge/lessons and future refinement expectations] carry corporate Australia's submarine industry has learnt from the Collins mistakes, said David Gould, the Englishman recruited to head up Australia's submarine program at the Defence Materiel Organisation.

That includes how to work with other countries, whose help we will inevitably need in designing the new submarine. As a 2011 RAND Corporation report found, we don't have the depth of expertise to design submarines ourselves, meaning we will need help from a country that specialises in conventional subs - Sweden [after the HDW 218SG decision Sweden is no longer an option] Germany, Spain or France.

Last time, the commercial agreement with the Collins' Swedish designer Kockums left Australia in a weak position with a lack of clarity as to what our rights were in regard to the intellectual property and the expectations on the Swedes.

"We won't be doing that again," Gould said. "This is about sovereignty - our sovereign ability to have the submarine that does what we demand of it ... so that when we put the crew into danger, we really do understand what we're doing. We haven't delegated that understanding to someone else."

And while we won't be designing everything ourselves, we will need the expertise to oversee and integrate all the work, says Rowan Moffitt - that means a generation of naval architects, systems engineers and systems integration experts.

"That's a quarter of a century of submarine building ... in which we will have to have an education and TAFE system producing the people we need through that period," Moffitt said.

Meanwhile, the clock is ticking on two fronts. First, the Collins will almost certainly need to continue service for an average of seven years beyond its original retirement date to avoid a capability gap around 2030. Gould maintains this can be managed.

There is also the question of the industry "valley of death". Whatever design Australia chooses, the submarines will be built in Adelaide, at the ASC. The industry association, the South Australian Defence Teaming Centre, this week welcomed [Australia's Defence] minister Johnston's apparent preference for the evolved Collins on the ground that work would start sooner.

The association's chief executive, Chris Burns, said unless the industry was "cutting steel" by early next decade, the Adelaide workforce, which is currently working on the Air Warfare Destroyer project, will find itself idle and those skills will be lost.

"The average age of a welder is about 50," he said. "It's very complex, specialist work and ... our true concern is that that work and those skills will be lost if there is a large gap between the end of the AWD [in 2019 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hobart-class_destroyer#Construction ] and the start of the future submarine." Moffitt points to an assessment by the Australian Industry Group that the future submarine program would employ about 5000 workers and 1000 Australian businesses, most of them small and medium-sized enterprises.

"It's not a one-off, stop-start project. By the time the 12th submarine is finished, it will be time to start looking for a replacement fleet. It could conceivably have no end so long as we seek to have 12 submarines in our inventory."

It nonetheless hinges on a future government being willing to commit the tens of billions of dollars necessary. That won't happen unless the Coalition starts to get defence spending back on track towards the target of 2 per cent of GDP.

With his cabinet colleagues desperate for budget savings, David Johnston will need every ounce of his strength for that fight."

-

Pete